-

Palestinians welcome ICC arrest warrants for Israeli officials

Palestinians welcome ICC arrest warrants for Israeli officials

-

Senegal ruling party wins parliamentary majority: provisional results

-

Fiji's Loganimasi in for banned Radradra against Ireland

Fiji's Loganimasi in for banned Radradra against Ireland

-

New proposal awaited in Baku on climate finance deal

-

Brazil police urge Bolsonaro's indictment for 2022 'coup' plot

Brazil police urge Bolsonaro's indictment for 2022 'coup' plot

-

NFL issues security alert to teams about home burglaries

-

Common water disinfectant creates potentially toxic byproduct: study

Common water disinfectant creates potentially toxic byproduct: study

-

Chimps are upping their tool game, says study

-

US actor Smollett's conviction for staged attack overturned

US actor Smollett's conviction for staged attack overturned

-

Fears rise of gender setbacks in global climate battle

-

'World's best coach' Gatland 'won't leave Wales' - Howley

'World's best coach' Gatland 'won't leave Wales' - Howley

-

Indian PM Modi highlights interest in Guyana's oil

-

Israel strikes kill 22 in Lebanon as Hezbollah targets south Israel

Israel strikes kill 22 in Lebanon as Hezbollah targets south Israel

-

Argentina lead Davis Cup holders Italy

-

West Bank city buries three Palestinians killed in Israeli raids

West Bank city buries three Palestinians killed in Israeli raids

-

Fairuz, musical icon of war-torn Lebanon, turns 90

-

Jones says Scotland need to beat Australia 'to be taken seriously'

Jones says Scotland need to beat Australia 'to be taken seriously'

-

Stock markets push higher but Ukraine tensions urge caution

-

IMF sees 'limited' impact of floods on Spain GDP growth

IMF sees 'limited' impact of floods on Spain GDP growth

-

Fresh Iran censure looms large over UN nuclear meeting

-

Volkswagen workers head towards strikes from December

Volkswagen workers head towards strikes from December

-

'More cautious' Dupont covers up in heavy Parisian snow before Argentina Test

-

UK sanctions Angola's Isabel dos Santos in graft crackdown

UK sanctions Angola's Isabel dos Santos in graft crackdown

-

Sales of existing US homes rise in October

-

Crunch time: What still needs to be hammered out at COP29?

Crunch time: What still needs to be hammered out at COP29?

-

Minister among 12 held over Serbia station collapse

-

Spurs boss Postecoglou hails 'outstanding' Bentancur despite Son slur

Spurs boss Postecoglou hails 'outstanding' Bentancur despite Son slur

-

South Sudan rejects 'malicious' report on Kiir family businesses

-

Kyiv claims 'crazy' Russia fired nuke-capable missile

Kyiv claims 'crazy' Russia fired nuke-capable missile

-

Australia defeat USA to reach Davis Cup semis

-

Spain holds 1st talks with Palestinian govt since recognising state

Spain holds 1st talks with Palestinian govt since recognising state

-

Stock markets waver as Nvidia, Ukraine tensions urge caution

-

Returning Vonn targets St Moritz World Cup races

Returning Vonn targets St Moritz World Cup races

-

Ramos nears PSG return as Sampaoli makes Rennes bow

-

Farrell hands Prendergast first Ireland start for Fiji Test

Farrell hands Prendergast first Ireland start for Fiji Test

-

Gaza strikes kill dozens as ICC issues Netanyahu arrest warrant

-

Famed Berlin theatre says cuts will sink it

Famed Berlin theatre says cuts will sink it

-

Stuttgart's Undav set to miss rest of year with hamstring injury

-

Cane, Perenara to make All Blacks farewells against Italy

Cane, Perenara to make All Blacks farewells against Italy

-

Kenya scraps Adani deals as Ruto attempts to reset presidency

-

French YouTuber takes on manga after conquering Everest

French YouTuber takes on manga after conquering Everest

-

Special reunion in store for France's Flament against 'hot-blooded' Argentina

-

'World of Warcraft' still going strong as it celebrates 20 years

'World of Warcraft' still going strong as it celebrates 20 years

-

Fritz pulls USA level with Australia in Davis Cup quarters

-

New Iran censure looms large over UN nuclear meeting

New Iran censure looms large over UN nuclear meeting

-

The first 'zoomed-in' image of a star outside our galaxy

-

ICC issues arrest warrants for Netanyahu, Gallant, Deif

ICC issues arrest warrants for Netanyahu, Gallant, Deif

-

Minister among 11 held over Serbia station collapse

-

Historic gold regalia returned to Ghana's king

Historic gold regalia returned to Ghana's king

-

Kyiv accuses Russia of launching intercontinental ballistic missile attack

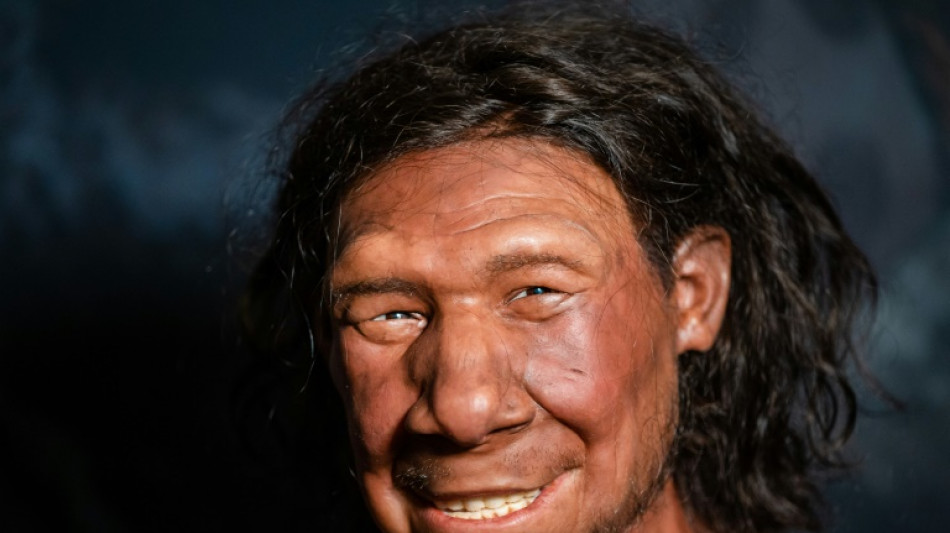

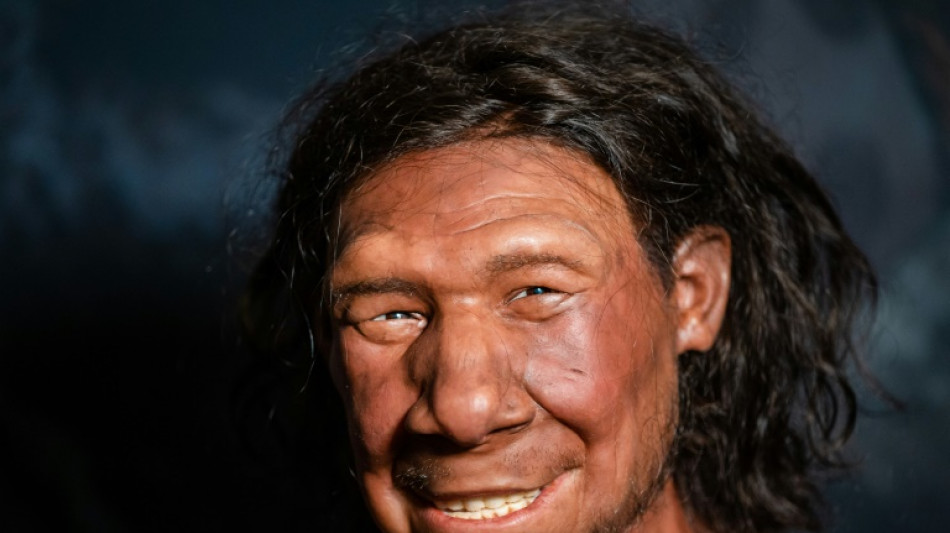

Was a lack of get-up-and-go the death of the Neanderthals?

A new study posits a very surprising answer to one of history's great mysteries -- what killed off the Neanderthals?

Could it be that they were unadventurous, insular homebodies who never strayed far enough from home?

Scientists studying the remains of a Neanderthal found in France said Wednesday that these human relatives were socially isolated from each other for tens of thousands of years, which could have fatally reduced their genetic diversity.

Up to now, the main theories for their demise were climate change, a disease outbreak, and even violence -- or interbreeding -- with Homo Sapiens.

Neanderthals populated Europe and Asia for a long time -- including a decent stint living alongside early modern humans -- until they abruptly died off 40,000 years ago.

That was the last moment when more than one species of human coexisted on Earth, French archaeologist Ludovic Slimak told AFP.

It was a "profoundly enigmatic moment, because we do not know how an entire humanity, which existed from Spain to Siberia, could suddenly go extinct," he said.

Slimak is the lead author of a new study in the journal Cell Genomics, which looked at the fossilised remains of a Neanderthal discovered in France's Rhone Valley in 2015.

The remains were found in Mandrin cave, which is known to have been home to both Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens over time.

The Neanderthal, dubbed Thorin in reference to the dwarf in J.R.R. Tolkien's "The Hobbit", is a rare find.

Thorin is the first Neanderthal unearthed in France since 1978 -- and one of only roughly 40 discovered in all of Eurasia.

- 50,000 years alone -

The archaeologists had spent a decade unsuccessfully trying to recover DNA from Mandrin cave when they found Thorin, Slimak said.

"As soon as the body came out of the ground," they sent a piece of molar to geneticists in Copenhagen for analysis, he added.

When the results came back, the team was stunned. Archaeological data had suggested the body was 40,000 to 45,000 years old, but the genomic analysis found it was from 105,000 years ago.

"One of the teams must have gotten it wrong," Slimak said.

It took seven years to get the story straight.

Analysing isotopes from Thorin's bones and teeth showed that he lived in an extremely cold climate, which matched an ice age only experienced by later Neanderthals around 40,000 years ago.

But Thorin's genome did not match those of previously discovered European Neanderthals at that time. Instead it resembled the genome of Neanderthals some 100,000 years ago, which had caused the confusion.

It turned out that Thorin was a member of an isolated and previously unknown community that had descended from some of Europe's earliest Neanderthal populations, the researchers said.

"The lineage leading to Thorin would have separated from the lineage leading to the other late Neanderthals around 105,000 years ago," senior study author Martin Sikora of the University of Copenhagen said in a statement.

This other lineage then spent a massive 50,000 years "without any genetic exchange with classic European Neanderthals," including some that only lived a two-week walk away, Slimak said.

- Dangers of inbreeding -

This kind of extended social isolation is unimaginable for the Neanderthals' cousins, the Homo Sapiens, particularly because the Rhone Valley then was a great migration corridor between northern Europe and the Mediterranean Sea.

Archaeological finds have long suggested that Neanderthals lived in a small area, ranging just a few dozen kilometres from their home.

Homo Sapiens, in comparison, had "infinitely larger" social circles, spreading over tens of thousands of square kilometres, Slimak said.

Neanderthals were also known to have lived in small groups -- so not venturing far likely meant there were not many options for a mate outside of their own family.

This kind of inbreeding reduces the genetic diversity in a species, which can spell doom over the long term.

Rather than single-handedly killing off the Neanderthals, their lack of intermingling could have made them more vulnerable to some of the other popular theories for their demise.

"When you are isolated for a long time, you limit the genetic variation that you have, which means you have less ability to adapt to changing climates and pathogens," said study co-author Tharsika Vimala, a population geneticist at the University of Copenhagen.

"It also limits you socially because you're not sharing knowledge or evolving as a population," she said.

P.Anderson--BTB